Bernard Dixey: A Lifetime Working on the Land

This is available as a word document; Bernard Dixey A Lifetime On The Land

Also as a pdf; Bernard Dixey A Lifetime On The Land

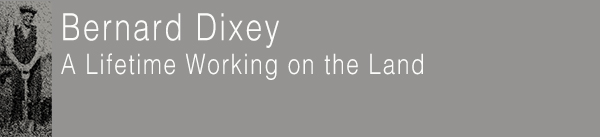

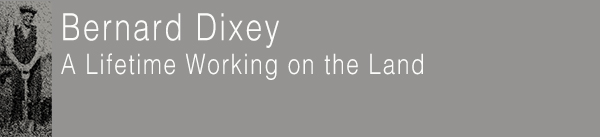

Bernard started work aged 14 in 1947. Apart from three years in the army on National service he worked until retirement on Hopgreen and Purley farms which are a mile or so north of Coggeshall towards Earls Colne. Both farms were were owned by J K King and mostly grew crops for seed. Kings were a famous firm of seedsmen, holders of the Royal Warrant and were founded in Coggeshall by John Kemp King in 1793. Kings had bought Hopgreen Farm in 1931 for £8 an acre.

(There are a number of gloriously specific words used in Bernard's account and there is a glossary at the end which is a resort for those of us who are not sons or daughter's of the soil)

From the left; the author Bernard Dixey, Jack Dixey, Peter Bowers, Howard Bowers, Ollie Parish.

Interrupted while taking up mangel plants from a nursery bed for replanting, probably taken in 1950

Introduction

Bernard writes;

Hopgreen was farmed by the Metcalfe family until they had to leave during the war. They didn't farm very well so were forced to go and this is when J K King took the farm on. I was still at school at that time. I remember the RAF men from the airfield helping with the harvest, mainly traving (stooking to some), loading the horse drawn wagons and building the stacks. I believe they enjoyed working away from their normal duties. We boys used to follow the binder with sticks to catch rabbits. From November to February Blackwell's threshing machine came in and us youngsters got our sticks out again; fine wire netting was put round the stack so the rats didn’t get away, then we waited and at a penny a tail it could be big money. At the end of the day or when the stack was finished the foreman would give us our pennies. There were five horses on the farm at that time, two at Purley and two at Hopgreen with a spare that worked between both farms.

I had my 14th birthday in February 1947 and I had been learning to be a carpenter, but that changed when Jim Bowers, the farm foreman, came to ask me if l would join Kings when I left school, which was at Easter, and I accepted. So at 14 my first job was spreading heaps of pig manure that were left because of the severe winter, I was joined by Peter Bowers who was also 14.

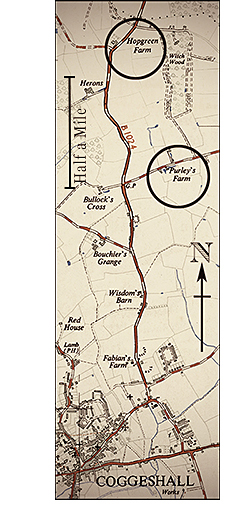

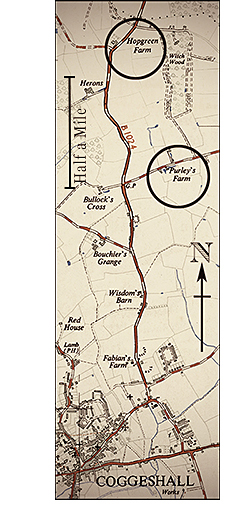

Fred Bowers' horses in the meadow behind Hopgreen farmhouse.

Jolly at the gate, Boxer, the grey spare horse and Smart almost hidden behind.

Tools

Up to 1953 we had to supply our own tools and only the best would do. To buy what was known as a patent hoe, which had a replaceable blade, we went to King the blacksmith at Great Tey to have one made, he made spare blades as well, he also made the iron dibber points that we needed. We put our own handles in which was usually a piece of straight hazel wood cut from a hedge. This had the bark peeled off then left to season, once seasoned it was sand-papered smooth and fitted to the hoe and then it was soaked with linseed oil to keep it soft to save us from getting blisters. We had the same process for the dibber (known to us as a deb) handles.

Next we need a bagging hook (known as a scrog hook) for this we went to an ironmongers in Kelvedon who sold Fussel Mells hooks which had a stronger crank to stand up to harder work.

Next we need a William Swift Roach back-bill-hook, (a chopper) and a light four tine fork (muck fork) and a carborundum these we bought at Rackhams the ironmonger in Church Street Coggeshall.

We then needed a Hank. We made these either from a length of quarter to half inch iron rod made into a hook with a wooden handle or from a piece of wood with two six inch nails in and a wooden handle. The hank was used to lift and roll when cutting peas or grass when hedge brushing.

We also had our own spade and shovel.

Bill Bowers with one of his pair of horses and the spare horse, a grey called Boxer

The Farming Year 1947-1951

Our work in those years was mainly by hand and horses. Kings had one tractor which was a Case LA petrol model, used mostly for ploughing and pulling the binder. The tractor ploughed the land on the big stetch, which was equal to six small stetches and used for corn crops. It wasn't allowed on the land after ploughing because of packing it down and it wasn't row crop.

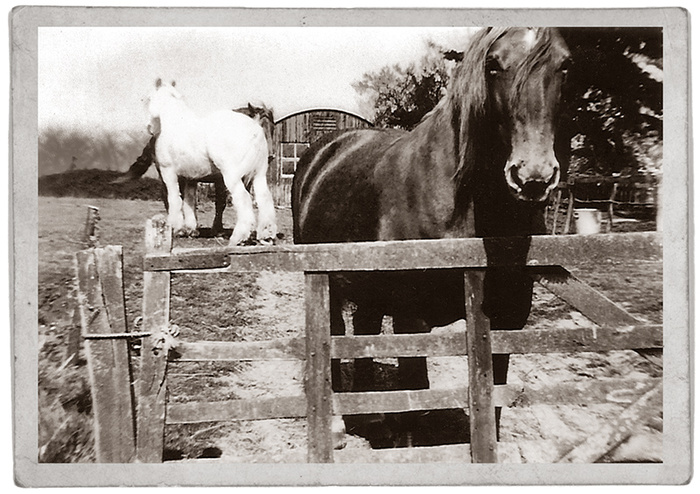

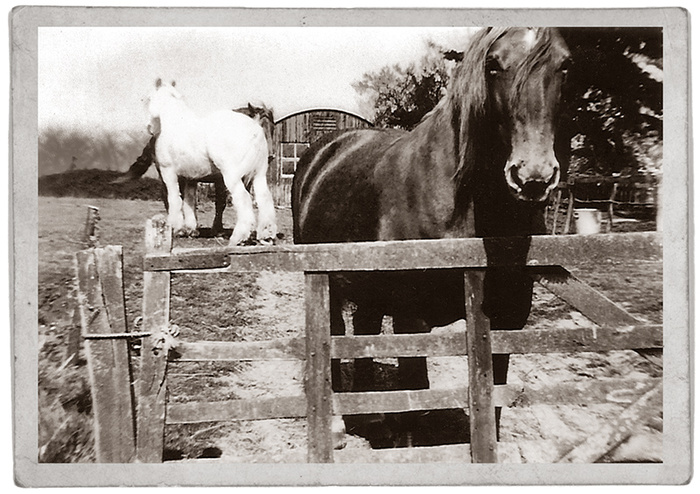

The horses used to plough all the land wanted for seven-feet six-inch stetch work. This was work for two pairs of horses with Fred and Bill Bowers as Ploughmen. After ploughing the one pair of horses would pull the land down for drilling with set of crab harrows, the other pair would pull the steerage Smyth drill and the odd-horse would pull a set of light harrows to cover the seed. The user was anyone who was free.

For crops such as Peas and Beans or any other crop on the small stetch was all worked the same way. The steerage drill was one man steering the horses and drill and one man walking at the back to lift the coulters and turn the seed on and off. The Smyth drill was used for all crops from turnip seed to broad beans, to do this we had two reversible barrels with two large cups on one, and two small cups on the second one. To put the right amount of seed per acre we had a box of cogs of various sizes, which worked on the main shaft or the barrel ends. To calibrate, the drill was jacked up and the wheel turned by hand the appropriate number of times for an acre, the seed was then weighed if not right, cogs would be changed until it was right. We also had to change the coulters, that is, twenty for corn on the big stetch or flat, eight for all peas, four for radish and three for runner beans and broad beans.

Next came the weeds, for this we used a Stetch Hoe drawn by two horses for the narrow rows or a Cottis horse hoe for the wide rows drawn by one horse. Both these had one man to guide them between the rows. Next we had to hand hoe in the rows this was usually done at least twice in the season.

We also had the job of walking through the cabbage, mangeI and swede giving them a pinch of sulphate of ammonia at each plant. If the sulphate was old stock we had cut it open and tip on the floor and break it up so we could use it.

When the weather was on the wet side and stopped the drilling or hoeing we used to clean out the horse and pig yards, this was all handwork and a horse and tumbrel (we called it tumble). The manure (muck) was transported to a site away from the houses and built into a dunghill (muck dungle) about four yards wide by four yards high, this was topped up as it sunk as it heated up. This was then left for about a year to heat up and rot.

When the crops grew too big to get into with the hand hoe one job we had was, if we had British Lion peas, was to walk through them with a cane and chop the top four/five inches off, if we left them they could grow to at least ten feet long and a poor yield.

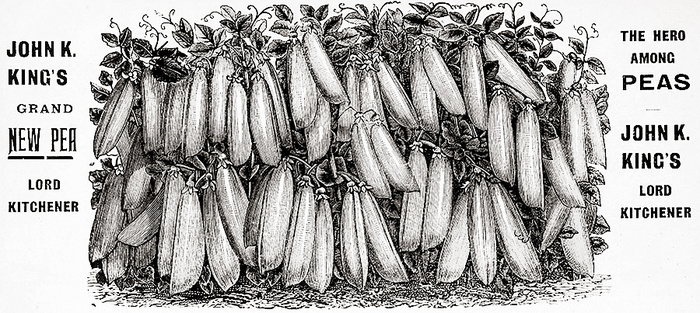

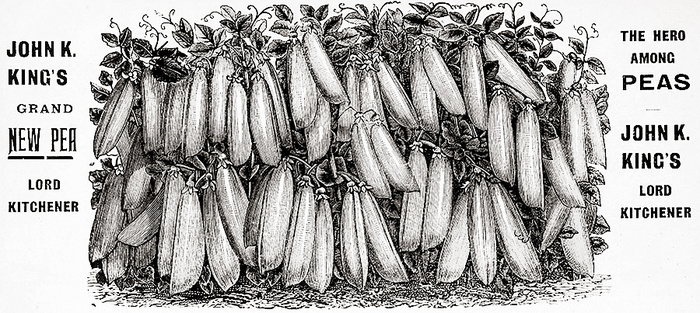

A beautiful engraving of an earlier variety of Pea, 'Lord Kitchener'

A classic J K King advert of 1900 in the heroic style.

King was always looking to link his business to royalty or to British hero's.

Time for one or two to have a holiday and others to start cutting about three feet of grass brew round the corn fields, This we did every year if possible. At the same time two of us would be tying hessian bags for the woman who were picking peas. These we carried off the field by horse and seed cart (a low high side cart) and laid on the ground in front of Hopgreen house. About four in the afternoon we loaded them on the lorry and Harry Bowers would take them during the night to Ashby’s stand at Covent Garden market, or maybe some to Goodenough’s stand. We had to use bags with their name on them. This was a period when we had some heavy thunderstorms.

Pea picking by an earlier generation. Mostly women and children working at a farm at Feering c1890.

Once the peas were off we used a horse rake to rake the pea rice into rows and then burn it, The horse plough came next to plough on the small stetch. When ploughed the land was left for a few days to settle then it was pulled down with horses and crab harrows, it was then marked with three rows to the stetch, this was done by leaving three ‘A’ hoes in the horse stetch hoe and a piece of sacking wrapped round the ‘A’ blades to mark three lines with no clods on them. While the horsemen were doing this the other men were busy pulling cabbage plants and trimming the longest roots off, this made it easier to put the plants in the dibber hole, the plants were taken from a bed which had been drilled earlier and grown to four to six inches high.

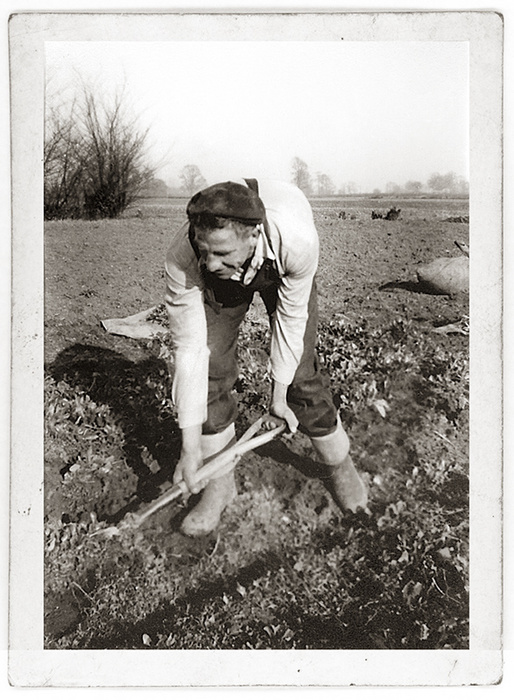

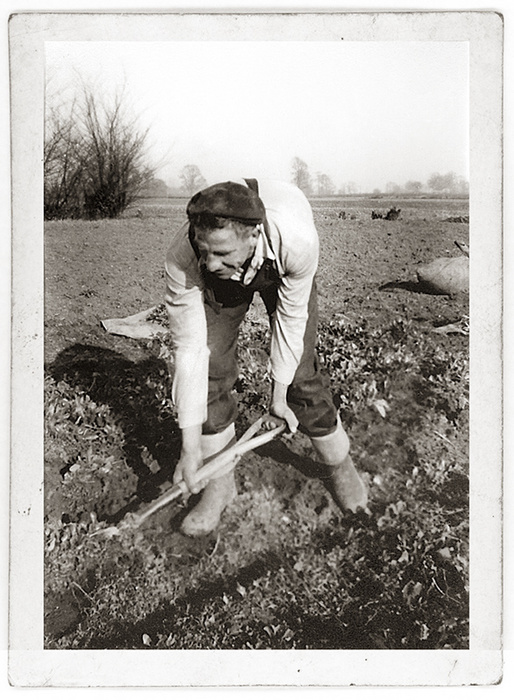

Harold Heard taking up or pulling mangel plants c1950.

Now it is July time and the ground is dry and we have six men and two boys to plant about ten acres of cabbages but first we had the offer of piece work (which we accepted) or day work and the foreman would offer a price which was a little more than day work, now this meant we had to work like hell to make a few more shillings pocket money, the two boys had a dropping bag each made from half a two hundredweight barley bag with a strap to hang round the neck, Each boy had three men to drop for and they kept to those three for the whole field, the idea was to drop the plants about sixteen inches apart for cabbage and twelve inches for mangel and swede. The spacing had be dead right for the men planting, we started a row by handing each one three plants to carry in the left hand in case one was needed. If we dropped them too far apart so it got too far to reach them they made us walk back and put things right but if it was the other way and they gained a hand full of plants they would call out and tell us that we were supposed to be spacing them not broadcasting them, this was usually in a language that made us feel like we didn't have a father. After that was over they placed the plants on the next row down for us to pick up on the way back. Once we had dropped out we had to help plant for the senior man first then the others in turn, when the last was out they had a rest while we made a start on the next rows. The worst times we had was when it was windy, it was nearly impossible to drop plants on the rows and if we managed to get them right, sometimes the wind would blow them about, if this happened we worked closer to the men so there was less chance of this happening.

Planting mangel plants, Colne Road Field. Before 1951

With the planting over we returned to day work pay and various jobs. One was to cut the wallflower seed of which we had about an acre beside the Colne Road in Overways Field. They were a perennial blood red variety highly perfumed. They were there for five years. Other jobs coming along was cutting seed peas with hook and hank. As the wheat and barley ripen we cut a strip round the fields wide enough for tractor and binder to travel without running on the crop (binder operated by Fred and Harry Bowers) for this we used a scythe with a long blade. It was really hot working along side the hedges. The binder was a Canadian Massey Harris, five foot cut, bought in the war.

By now the seed peas had possibly been turned with a sheaf fork a few times to dry out due to rain. If dry enough we used the two horse wagons to carry them to be stacked either at Hopgreen or Purley. One wagon was ex-army 1914 war, the other was a Suffolk corn wagon. While this was being done any spare men were traving behind the binder.

When the peas were on the stack we had the Cabbage seed to cut, for this we needed a scrog hook, a very big left hand and a bundle of string -this was saved from last year's corn sheaves which were threshed out during the winter) which we carried on a string tied round the waist, We had an order of work; which was the senior man, Dick Smith, took the first stetch (three rows) when he had cut and tied one sheaf the next did the same, this was done by each man with the two boys at the end. This meant we were at least five or six sheaves behind the leader. It was God help us if we got ahead of any of the men, it was the law of the land and it wasn't the done thing in those days. Next came the Swede seed this was the same rules as cabbage except it was four rows to a stetch.

Carting the last sheaves. Taken in 1951 at another local seedgrower's farm, that of T Cullen.

With the Cabbage and Swede cut and laying out to dry the wagons came out again this time to cart the cereals to stack in the stackyard. Once we have two or three stacks finished Dick Smith would thatch them to keep them to the end of the season. Except maybe a crop of wheat or barley was needed urgent Blackwell’s thresher would stand in the corner of the field and we carted the sheaves to the machine, The seed was weighed at eighteen stone for wheat or sixteen stone for barley which was loaded on Harry Bowers lorry and taken to Kings warehouse. The straw was baled behind the thresher. Blackwell supplied two men one of them was in charge of the steam engine which was a small Garret, the other one was in charge of the thresher and baler to make sure they are kept oiled and greased, his other job was feeder on the Drum (thresher) he stood knee deep in a box just behind the beaters with his arms out and make sure the sheaves thinned out. My job was to stand beside him and pick the sheaves up and drop them on his arms at the same time cutting the string near the knot and saving it to tie sacks with.

The last to be cut was the Mangel seed, this didn't need string as it held together (this is where the big hands came in handy) the more we could collect in one handful the better it held together, being so late in season we had to stand it up in traves (stooks) of four bundles the reason for this was so we could use a pitch fork, (a large fork with long tines and extra long handle) to pick the four bundles up in one lot to save knocking seed off by parting them. We have had years when mangel has been stacked with a white frost on the top, this was alright as the coarse stems didn't pack down solid which allowed it to dry out on the stack. This was thatched and then threshed early new year in time for early plant beds.

Thrashing underway with a pitcher at Curd Hall farm in Coggeshall, date c1951.

After about two years Blackwell bought a self-feeder thresher, which meant I was alone on top and had to cut the bends (string) at the knot and drop the sheaf on to a small conveyer belt, which thinned it out and fed into the beaters. I know what it feel like to have mice run inside my trouser leg and come out of my shirt collar when standing on the thresher. At the same time Old Sid Blackwell was building a self feeder baler, when this came out it didn't need a man to feed it, This meant we needed two less men to operate the whole system.

The alternative to the baler was an elevator (locally called a pitcher) this was set behind the thresher for the straw to drop into it and then taken up to the straw stack. The pitcher had two extensions to bolt onto the rack so it could be raised between 60 and 70 degrees to make a good height stack, to build a stack a minimum of two men were needed, one kept to the side to lay the outside and tread it down while the second man moved the straw from the pitcher and passed half to the stacker and half he placed round the second row just overlapping the first to tie it in, then he filled the middle so as to tie the whole laying together. This was repeated from the base to the top until only room was left for one to fill the last centre hole in, while standing on a ladder. If the straw was kept for a long period it was thatched after it had a few days to settle.

We used to grow runner beans for seed; these we kept free of weeds by going through them with one horse and a Cottis hoe between the rows, then we did the rows with a hand hoe. When ready to harvest we cut them by hand with a cranked scrog hook (bagging hook) and a two tine crome so we could cut and roll the beans into small heaps we could handle easy with a two tine fork, when cutting was over we put them on tripods about the field or if needed for ploughing we stacked them round the farm yard, sometimes we moved them on to larger stacks when they had dried out so they could be thatched when settled and kept to thresh out later.

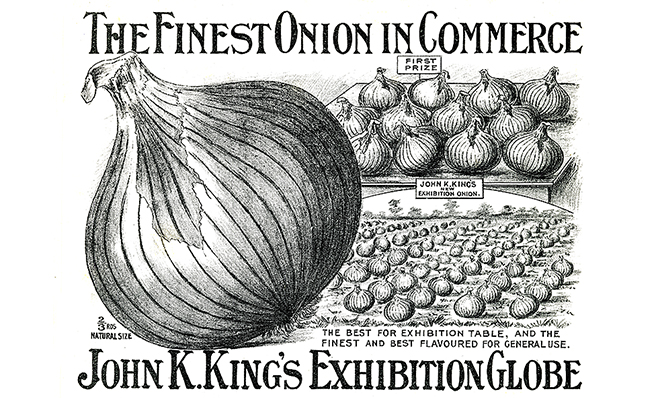

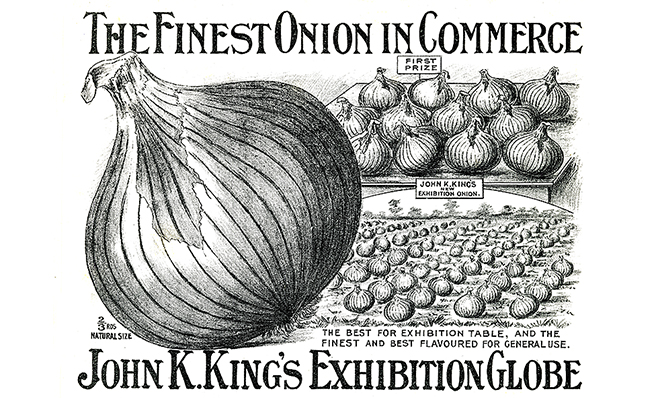

John K King's 'Exhibition Globe'the finest onion in commerce.

Onion seed was another small crop we grew, when the seed heads were ready to cut we had a big stack cloth laid out in the stack yard so we could put a thin laying of heads on it to dry out, now someone had the job of rolling this lot up at night or when it started to rain and opening up in the mornings, this carried on until most of the seed fell out and then we threshed the rest out with a flail. Which we had to learn to use but after cracking our knuckles a few times between the two pieces of wood we soon learn how to swing the short end safely.

The winter was spent hedge brushing ie cutting the grass round the fields and in the ditches (scrog hook and hank). The biggest hedges were cut down in rotation (bill hook, axe, bow saw) and some ditches were dug out each year, (narrow spade and shovel). We also cleaned the outlets at the ends of the water furrows that were dug to take the top water off the fields.

In November 1951 Bernard had to leave the farm to do National Service. He was away for a full three years, returning in December 1954. What happened on the farms while he was away and when he started work again follows in Part 2.

Glossary

Glossary

Back billhook – a straight-bladed axe which curves to a tooth at its end often used for hedging.

Brew – Self-seeded weeds and grass

Carborundum – a sharpening stone

Cottis horse hoe – a hoe where the spacing between the blades was adjustable. William Cottis & Sons were founded in Epping in 1858

Crab harrow - used to break up the soil to produce a tilth for sowing.

Crome - two-tined fork, the fork angled at 90 degrees to its (long) handle.

Deb – Also called a dibber – used to make a hole for a plant or a seed.

Hank – An iron rod shaped into a curve with a handle used to gather and hold.

Hedge brushing – cutting the grass around the fields and in the ditches.

Muck dungle – a muck heap

Patent hoe – a hoe where the head could be changed when worn.

Pea-rice – remains of the pea plant when the peas had been picked.

Pitcher – a mechanical elevator used to lift crop to a stack.

Rowcrop – Crop planted in rows wide enough to allow a tractor to run along them.

Sheaf fork – a two or three tined fork on a wooden handle

Stetch – A ridge formed by a plough or to form into ridges with a plough.

Scrog hook - a curved blade with a wooden handle, sometimes called a sickle elsewhere.

Smyth drill - Horse drawn seed drill for a wide range of seeds. Could be adjusted for the spacing between the rows sown and for the quantity of seed sown per acre.

Traves - local word for stooks.

Traving – also called stooking, to stand the cut crop together in the field.

Tumble – a tumbrel, a two-wheeled cart used for manure that can be tilted to discharge the load.

Water furrows – furrows made to drain the surface water off a field.

Staff on the farm up to and including 1947

Jim Bowers, Foreman. Lived Hopgreen House. He was bombed out of Purley in the War. He retired about 1949 and Fred Bowers took his place.

Fred Bowers, horseman at Hopgreen. Lived Earls Colne at the time. He moved in with his parents at Hopgreen house when he became foreman.

Bill Bowers, horseman at Purley. Lived in Colne Road, Coggeshall next to the reservoir.

Dick Smith, labourer, Coggeshall Road, Earls Colne - on the left just past CA Blackwell’s. Retired about 1949.

Herbert Smith, labourer, Ditto. Left end of 1948.

Walter Sharpe, labourer. Lived in a cottage on School Corner Coggeshall. Retired in 1946.

Roy Carder, labourer lived in Earls Colne Village, left in 1947

Harold Heard, labourer lived end of Curds Road on Coggeshall Road, Earls Colne. Left 1946, returned 1948.

Arthur Heard, Ditto, left 1948.

Mike Creswell, labourer lived in Coggeshall, retired 1946.

Jack Dixey, labourer, lived second house from Hopgreen in Earls Colne. Joined 1946

Bernard Dixey, as above, joined 1947, age 14, at Easter. [National Service] Deferred from February to November 1951 then joined the Army. Returned to Kings, December 1954.

Harry Bowers, tractor driver and lorry driver, lived in Colne Road next door to Bill Bowers. Had a Kings lorry standing at Hopgreen and used to carry for the Warehouse when they were busy and take peas to London market sometimes. Died around 1949 /50.

Peter Bowers, labourer, Harry’s son, joined 1947 age 14 at Easter. Left early 1951 to join RAF.

Ollie Parish, labourer, joined 1948, lived in Tilkey Road, Coggeshall. He retired some time in the 60s.

Replacement Staff

Howard Bowers, Bill’s son, joined Easter 1948 age 15, left early 1951 to join the Army.

Douglas Bowers, Fred’s nephew, lived with Fred at Hopgreen. Joined 1948, left late 1950.

Others to join over the years, (I have no dates for) were Wally Gibson and his son who lived in a Kings House opposite Gatehouse Farm, in Coggeshall Road, Earls Colne. When they left Stan Taylor joined and moved into the same house.

George Lawrence lived behind the stitching factory in Coggeshall. George was a part timer and helped wherever he was needed.

Also as a pdf; Bernard Dixey A Lifetime On The Land

Bernard started work aged 14 in 1947. Apart from three years in the army on National service he worked until retirement on Hopgreen and Purley farms which are a mile or so north of Coggeshall towards Earls Colne. Both farms were were owned by J K King and mostly grew crops for seed. Kings were a famous firm of seedsmen, holders of the Royal Warrant and were founded in Coggeshall by John Kemp King in 1793. Kings had bought Hopgreen Farm in 1931 for £8 an acre.

(There are a number of gloriously specific words used in Bernard's account and there is a glossary at the end which is a resort for those of us who are not sons or daughter's of the soil)

Interrupted while taking up mangel plants from a nursery bed for replanting, probably taken in 1950

Introduction

Bernard writes;

Hopgreen was farmed by the Metcalfe family until they had to leave during the war. They didn't farm very well so were forced to go and this is when J K King took the farm on. I was still at school at that time. I remember the RAF men from the airfield helping with the harvest, mainly traving (stooking to some), loading the horse drawn wagons and building the stacks. I believe they enjoyed working away from their normal duties. We boys used to follow the binder with sticks to catch rabbits. From November to February Blackwell's threshing machine came in and us youngsters got our sticks out again; fine wire netting was put round the stack so the rats didn’t get away, then we waited and at a penny a tail it could be big money. At the end of the day or when the stack was finished the foreman would give us our pennies. There were five horses on the farm at that time, two at Purley and two at Hopgreen with a spare that worked between both farms.

I had my 14th birthday in February 1947 and I had been learning to be a carpenter, but that changed when Jim Bowers, the farm foreman, came to ask me if l would join Kings when I left school, which was at Easter, and I accepted. So at 14 my first job was spreading heaps of pig manure that were left because of the severe winter, I was joined by Peter Bowers who was also 14.

Jolly at the gate, Boxer, the grey spare horse and Smart almost hidden behind.

Tools

Up to 1953 we had to supply our own tools and only the best would do. To buy what was known as a patent hoe, which had a replaceable blade, we went to King the blacksmith at Great Tey to have one made, he made spare blades as well, he also made the iron dibber points that we needed. We put our own handles in which was usually a piece of straight hazel wood cut from a hedge. This had the bark peeled off then left to season, once seasoned it was sand-papered smooth and fitted to the hoe and then it was soaked with linseed oil to keep it soft to save us from getting blisters. We had the same process for the dibber (known to us as a deb) handles.

Next we need a bagging hook (known as a scrog hook) for this we went to an ironmongers in Kelvedon who sold Fussel Mells hooks which had a stronger crank to stand up to harder work.

Next we need a William Swift Roach back-bill-hook, (a chopper) and a light four tine fork (muck fork) and a carborundum these we bought at Rackhams the ironmonger in Church Street Coggeshall.

We then needed a Hank. We made these either from a length of quarter to half inch iron rod made into a hook with a wooden handle or from a piece of wood with two six inch nails in and a wooden handle. The hank was used to lift and roll when cutting peas or grass when hedge brushing.

We also had our own spade and shovel.

The Farming Year 1947-1951

Our work in those years was mainly by hand and horses. Kings had one tractor which was a Case LA petrol model, used mostly for ploughing and pulling the binder. The tractor ploughed the land on the big stetch, which was equal to six small stetches and used for corn crops. It wasn't allowed on the land after ploughing because of packing it down and it wasn't row crop.

The horses used to plough all the land wanted for seven-feet six-inch stetch work. This was work for two pairs of horses with Fred and Bill Bowers as Ploughmen. After ploughing the one pair of horses would pull the land down for drilling with set of crab harrows, the other pair would pull the steerage Smyth drill and the odd-horse would pull a set of light harrows to cover the seed. The user was anyone who was free.

For crops such as Peas and Beans or any other crop on the small stetch was all worked the same way. The steerage drill was one man steering the horses and drill and one man walking at the back to lift the coulters and turn the seed on and off. The Smyth drill was used for all crops from turnip seed to broad beans, to do this we had two reversible barrels with two large cups on one, and two small cups on the second one. To put the right amount of seed per acre we had a box of cogs of various sizes, which worked on the main shaft or the barrel ends. To calibrate, the drill was jacked up and the wheel turned by hand the appropriate number of times for an acre, the seed was then weighed if not right, cogs would be changed until it was right. We also had to change the coulters, that is, twenty for corn on the big stetch or flat, eight for all peas, four for radish and three for runner beans and broad beans.

Next came the weeds, for this we used a Stetch Hoe drawn by two horses for the narrow rows or a Cottis horse hoe for the wide rows drawn by one horse. Both these had one man to guide them between the rows. Next we had to hand hoe in the rows this was usually done at least twice in the season.

We also had the job of walking through the cabbage, mangeI and swede giving them a pinch of sulphate of ammonia at each plant. If the sulphate was old stock we had cut it open and tip on the floor and break it up so we could use it.

When the weather was on the wet side and stopped the drilling or hoeing we used to clean out the horse and pig yards, this was all handwork and a horse and tumbrel (we called it tumble). The manure (muck) was transported to a site away from the houses and built into a dunghill (muck dungle) about four yards wide by four yards high, this was topped up as it sunk as it heated up. This was then left for about a year to heat up and rot.

When the crops grew too big to get into with the hand hoe one job we had was, if we had British Lion peas, was to walk through them with a cane and chop the top four/five inches off, if we left them they could grow to at least ten feet long and a poor yield.

A classic J K King advert of 1900 in the heroic style.

King was always looking to link his business to royalty or to British hero's.

Time for one or two to have a holiday and others to start cutting about three feet of grass brew round the corn fields, This we did every year if possible. At the same time two of us would be tying hessian bags for the woman who were picking peas. These we carried off the field by horse and seed cart (a low high side cart) and laid on the ground in front of Hopgreen house. About four in the afternoon we loaded them on the lorry and Harry Bowers would take them during the night to Ashby’s stand at Covent Garden market, or maybe some to Goodenough’s stand. We had to use bags with their name on them. This was a period when we had some heavy thunderstorms.

Once the peas were off we used a horse rake to rake the pea rice into rows and then burn it, The horse plough came next to plough on the small stetch. When ploughed the land was left for a few days to settle then it was pulled down with horses and crab harrows, it was then marked with three rows to the stetch, this was done by leaving three ‘A’ hoes in the horse stetch hoe and a piece of sacking wrapped round the ‘A’ blades to mark three lines with no clods on them. While the horsemen were doing this the other men were busy pulling cabbage plants and trimming the longest roots off, this made it easier to put the plants in the dibber hole, the plants were taken from a bed which had been drilled earlier and grown to four to six inches high.

Now it is July time and the ground is dry and we have six men and two boys to plant about ten acres of cabbages but first we had the offer of piece work (which we accepted) or day work and the foreman would offer a price which was a little more than day work, now this meant we had to work like hell to make a few more shillings pocket money, the two boys had a dropping bag each made from half a two hundredweight barley bag with a strap to hang round the neck, Each boy had three men to drop for and they kept to those three for the whole field, the idea was to drop the plants about sixteen inches apart for cabbage and twelve inches for mangel and swede. The spacing had be dead right for the men planting, we started a row by handing each one three plants to carry in the left hand in case one was needed. If we dropped them too far apart so it got too far to reach them they made us walk back and put things right but if it was the other way and they gained a hand full of plants they would call out and tell us that we were supposed to be spacing them not broadcasting them, this was usually in a language that made us feel like we didn't have a father. After that was over they placed the plants on the next row down for us to pick up on the way back. Once we had dropped out we had to help plant for the senior man first then the others in turn, when the last was out they had a rest while we made a start on the next rows. The worst times we had was when it was windy, it was nearly impossible to drop plants on the rows and if we managed to get them right, sometimes the wind would blow them about, if this happened we worked closer to the men so there was less chance of this happening.

With the planting over we returned to day work pay and various jobs. One was to cut the wallflower seed of which we had about an acre beside the Colne Road in Overways Field. They were a perennial blood red variety highly perfumed. They were there for five years. Other jobs coming along was cutting seed peas with hook and hank. As the wheat and barley ripen we cut a strip round the fields wide enough for tractor and binder to travel without running on the crop (binder operated by Fred and Harry Bowers) for this we used a scythe with a long blade. It was really hot working along side the hedges. The binder was a Canadian Massey Harris, five foot cut, bought in the war.

By now the seed peas had possibly been turned with a sheaf fork a few times to dry out due to rain. If dry enough we used the two horse wagons to carry them to be stacked either at Hopgreen or Purley. One wagon was ex-army 1914 war, the other was a Suffolk corn wagon. While this was being done any spare men were traving behind the binder.

When the peas were on the stack we had the Cabbage seed to cut, for this we needed a scrog hook, a very big left hand and a bundle of string -this was saved from last year's corn sheaves which were threshed out during the winter) which we carried on a string tied round the waist, We had an order of work; which was the senior man, Dick Smith, took the first stetch (three rows) when he had cut and tied one sheaf the next did the same, this was done by each man with the two boys at the end. This meant we were at least five or six sheaves behind the leader. It was God help us if we got ahead of any of the men, it was the law of the land and it wasn't the done thing in those days. Next came the Swede seed this was the same rules as cabbage except it was four rows to a stetch.

With the Cabbage and Swede cut and laying out to dry the wagons came out again this time to cart the cereals to stack in the stackyard. Once we have two or three stacks finished Dick Smith would thatch them to keep them to the end of the season. Except maybe a crop of wheat or barley was needed urgent Blackwell’s thresher would stand in the corner of the field and we carted the sheaves to the machine, The seed was weighed at eighteen stone for wheat or sixteen stone for barley which was loaded on Harry Bowers lorry and taken to Kings warehouse. The straw was baled behind the thresher. Blackwell supplied two men one of them was in charge of the steam engine which was a small Garret, the other one was in charge of the thresher and baler to make sure they are kept oiled and greased, his other job was feeder on the Drum (thresher) he stood knee deep in a box just behind the beaters with his arms out and make sure the sheaves thinned out. My job was to stand beside him and pick the sheaves up and drop them on his arms at the same time cutting the string near the knot and saving it to tie sacks with.

The last to be cut was the Mangel seed, this didn't need string as it held together (this is where the big hands came in handy) the more we could collect in one handful the better it held together, being so late in season we had to stand it up in traves (stooks) of four bundles the reason for this was so we could use a pitch fork, (a large fork with long tines and extra long handle) to pick the four bundles up in one lot to save knocking seed off by parting them. We have had years when mangel has been stacked with a white frost on the top, this was alright as the coarse stems didn't pack down solid which allowed it to dry out on the stack. This was thatched and then threshed early new year in time for early plant beds.

After about two years Blackwell bought a self-feeder thresher, which meant I was alone on top and had to cut the bends (string) at the knot and drop the sheaf on to a small conveyer belt, which thinned it out and fed into the beaters. I know what it feel like to have mice run inside my trouser leg and come out of my shirt collar when standing on the thresher. At the same time Old Sid Blackwell was building a self feeder baler, when this came out it didn't need a man to feed it, This meant we needed two less men to operate the whole system.

The alternative to the baler was an elevator (locally called a pitcher) this was set behind the thresher for the straw to drop into it and then taken up to the straw stack. The pitcher had two extensions to bolt onto the rack so it could be raised between 60 and 70 degrees to make a good height stack, to build a stack a minimum of two men were needed, one kept to the side to lay the outside and tread it down while the second man moved the straw from the pitcher and passed half to the stacker and half he placed round the second row just overlapping the first to tie it in, then he filled the middle so as to tie the whole laying together. This was repeated from the base to the top until only room was left for one to fill the last centre hole in, while standing on a ladder. If the straw was kept for a long period it was thatched after it had a few days to settle.

We used to grow runner beans for seed; these we kept free of weeds by going through them with one horse and a Cottis hoe between the rows, then we did the rows with a hand hoe. When ready to harvest we cut them by hand with a cranked scrog hook (bagging hook) and a two tine crome so we could cut and roll the beans into small heaps we could handle easy with a two tine fork, when cutting was over we put them on tripods about the field or if needed for ploughing we stacked them round the farm yard, sometimes we moved them on to larger stacks when they had dried out so they could be thatched when settled and kept to thresh out later.

Onion seed was another small crop we grew, when the seed heads were ready to cut we had a big stack cloth laid out in the stack yard so we could put a thin laying of heads on it to dry out, now someone had the job of rolling this lot up at night or when it started to rain and opening up in the mornings, this carried on until most of the seed fell out and then we threshed the rest out with a flail. Which we had to learn to use but after cracking our knuckles a few times between the two pieces of wood we soon learn how to swing the short end safely.

The winter was spent hedge brushing ie cutting the grass round the fields and in the ditches (scrog hook and hank). The biggest hedges were cut down in rotation (bill hook, axe, bow saw) and some ditches were dug out each year, (narrow spade and shovel). We also cleaned the outlets at the ends of the water furrows that were dug to take the top water off the fields.

In November 1951 Bernard had to leave the farm to do National Service. He was away for a full three years, returning in December 1954. What happened on the farms while he was away and when he started work again follows in Part 2.

Glossary

Glossary Back billhook – a straight-bladed axe which curves to a tooth at its end often used for hedging.

Brew – Self-seeded weeds and grass

Carborundum – a sharpening stone

Cottis horse hoe – a hoe where the spacing between the blades was adjustable. William Cottis & Sons were founded in Epping in 1858

Crab harrow - used to break up the soil to produce a tilth for sowing.

Crome - two-tined fork, the fork angled at 90 degrees to its (long) handle.

Deb – Also called a dibber – used to make a hole for a plant or a seed.

Hank – An iron rod shaped into a curve with a handle used to gather and hold.

Hedge brushing – cutting the grass around the fields and in the ditches.

Muck dungle – a muck heap

Patent hoe – a hoe where the head could be changed when worn.

Pea-rice – remains of the pea plant when the peas had been picked.

Pitcher – a mechanical elevator used to lift crop to a stack.

Rowcrop – Crop planted in rows wide enough to allow a tractor to run along them.

Sheaf fork – a two or three tined fork on a wooden handle

Stetch – A ridge formed by a plough or to form into ridges with a plough.

Scrog hook - a curved blade with a wooden handle, sometimes called a sickle elsewhere.

Smyth drill - Horse drawn seed drill for a wide range of seeds. Could be adjusted for the spacing between the rows sown and for the quantity of seed sown per acre.

Traves - local word for stooks.

Traving – also called stooking, to stand the cut crop together in the field.

Tumble – a tumbrel, a two-wheeled cart used for manure that can be tilted to discharge the load.

Water furrows – furrows made to drain the surface water off a field.

Staff on the farm up to and including 1947

Jim Bowers, Foreman. Lived Hopgreen House. He was bombed out of Purley in the War. He retired about 1949 and Fred Bowers took his place.

Fred Bowers, horseman at Hopgreen. Lived Earls Colne at the time. He moved in with his parents at Hopgreen house when he became foreman.

Bill Bowers, horseman at Purley. Lived in Colne Road, Coggeshall next to the reservoir.

Dick Smith, labourer, Coggeshall Road, Earls Colne - on the left just past CA Blackwell’s. Retired about 1949.

Herbert Smith, labourer, Ditto. Left end of 1948.

Walter Sharpe, labourer. Lived in a cottage on School Corner Coggeshall. Retired in 1946.

Roy Carder, labourer lived in Earls Colne Village, left in 1947

Harold Heard, labourer lived end of Curds Road on Coggeshall Road, Earls Colne. Left 1946, returned 1948.

Arthur Heard, Ditto, left 1948.

Mike Creswell, labourer lived in Coggeshall, retired 1946.

Jack Dixey, labourer, lived second house from Hopgreen in Earls Colne. Joined 1946

Bernard Dixey, as above, joined 1947, age 14, at Easter. [National Service] Deferred from February to November 1951 then joined the Army. Returned to Kings, December 1954.

Harry Bowers, tractor driver and lorry driver, lived in Colne Road next door to Bill Bowers. Had a Kings lorry standing at Hopgreen and used to carry for the Warehouse when they were busy and take peas to London market sometimes. Died around 1949 /50.

Peter Bowers, labourer, Harry’s son, joined 1947 age 14 at Easter. Left early 1951 to join RAF.

Ollie Parish, labourer, joined 1948, lived in Tilkey Road, Coggeshall. He retired some time in the 60s.

Replacement Staff

Howard Bowers, Bill’s son, joined Easter 1948 age 15, left early 1951 to join the Army.

Douglas Bowers, Fred’s nephew, lived with Fred at Hopgreen. Joined 1948, left late 1950.

Others to join over the years, (I have no dates for) were Wally Gibson and his son who lived in a Kings House opposite Gatehouse Farm, in Coggeshall Road, Earls Colne. When they left Stan Taylor joined and moved into the same house.

George Lawrence lived behind the stitching factory in Coggeshall. George was a part timer and helped wherever he was needed.

Comments

By Roddy Miller: Bernie! Good to see you still alive I recall Bernie marrying and living in Kings Yard His new wife used to run out of the house giggling and Bernie would sweep her up and take her back inside He always wore a black beret Good to see his memories

By Roddy Miller: Bernie! Good to see you still alive I recall Bernie marrying and living in Kings Yard His new wife used to run out of the house giggling and Bernie would sweep her up and take her back inside He always wore a black beret Good to see his memories By jill barrett nee ladhams: born in wisdoms cottages colne road brings back memories thankyou

By jill barrett nee ladhams: born in wisdoms cottages colne road brings back memories thankyou By Cynthia Williams nee Bowers: I have many happy memories of Hopgreen and always said it was my second home as I spent a lot of time there with my aunt and uncle Mr and Mrs Fred Bowers. Your dad was always very kind and let me help rounding up the pigs on market day. I must have got in the way Ha!Ha! Thank you for a most interesting history.

By Cynthia Williams nee Bowers: I have many happy memories of Hopgreen and always said it was my second home as I spent a lot of time there with my aunt and uncle Mr and Mrs Fred Bowers. Your dad was always very kind and let me help rounding up the pigs on market day. I must have got in the way Ha!Ha! Thank you for a most interesting history. By Roddy Miller Chris Millers boy: Dammit Bernie I still have my old chaps (Jack Smith of Brick Kiln Gt Tey) Fussel Mells Scrog hook and I still use it!

By Roddy Miller Chris Millers boy: Dammit Bernie I still have my old chaps (Jack Smith of Brick Kiln Gt Tey) Fussel Mells Scrog hook and I still use it! By Cheryl Phillips nee Saunders: Really enjoyed reading your memories Bernard and seeing the lovely photos. When we moved to Purley Farm house in 1990 you were still working there. We lived there for nearly 30 years bringing up our family and hauling for J K Kings until they sold the company. We loved living there until the council gave Change of use to the barn in the farm yard to a school and it completely changed the quite lane. I tried to find photos of Purley farm house before it got bombed but couldn't. I only found one of the rubble after the bomb. If anyone has a photo I would love to see it.

By Cheryl Phillips nee Saunders: Really enjoyed reading your memories Bernard and seeing the lovely photos. When we moved to Purley Farm house in 1990 you were still working there. We lived there for nearly 30 years bringing up our family and hauling for J K Kings until they sold the company. We loved living there until the council gave Change of use to the barn in the farm yard to a school and it completely changed the quite lane. I tried to find photos of Purley farm house before it got bombed but couldn't. I only found one of the rubble after the bomb. If anyone has a photo I would love to see it. By Andy Brown: A great insight into tools used on the farm. And from this it would appear that I have a *hank* with the iron curved rod as described above. Cheers Andy

By Andy Brown: A great insight into tools used on the farm. And from this it would appear that I have a *hank* with the iron curved rod as described above. Cheers Andy By Katherine Draper: It lovely to hear what my grandad Bernard Dixey got up too while he was at the farm can remember going to the farm when I was little to see him miss him

By Katherine Draper: It lovely to hear what my grandad Bernard Dixey got up too while he was at the farm can remember going to the farm when I was little to see him miss him